René Higuita was not only fearless on the pitch, but off it too. Redefining the role of the goalkeeper with his mad antics, and looking good whilst doing it, El Loco truly earned his nickname.

It was in the midst of extreme poverty and relentless criminal activity where René Higuita discovered his love for football.

Born in Castilla, Medellín, Colombia in 1966, he was raised by his grandmother after his mothers sudden passing when he was just a little boy.

He trained tirelessly on the dry, grassless local pitch, illuminated by floodlights installed by Pablo Escobar.

Starting off as a prolific striker at youth level, it’s no secret where René got his enviable composure and jinking footwork from, which helped him notch 40 goals during his career as a goalkeeper.

He quickly etched his way into Colombian hearts, with his iconic curly black hair cascading down to his shoulders combined with his bushy moustache and cheesy grin.

Famous for his erratic yet revolutionary style of play, often embarking on mazy runs deep into the opponent’s half and sitting in midfield when his team had possession, Colombia quickly realised it had birthed a goalkeeper different to all others.

He was expeditiously rewarded with the nickname El Loco.

When asked where René Higuita ranks when it comes to Colombian’s greatest ever footballers, Colombian writer Daniel Acosta seemed almost offended that I’d asked him such a thing.

“Footballers?” He chuckled.

“With René, we are talking not just about the best Colombian footballers, we are talking about the best Colombian people!”

“The things he did in a Colombia shirt at the time he did them was exactly what our people needed and helped to transform our country’s image in the eyes of the rest of the world.”

Daniel is referring to the rise of powerful drug cartels in Colombia which controlled the global cocaine trade, primarily in the 1980’s and 90’s.

“Colombians were seen as crooks and drug lords, the national team gave the reputation of our country a shot at redemption.”

By the time the Italy 1990 World Cup rolled around, a 23-year-old René had already enjoyed five years of professional football in Colombia, four being with giants Atlético Nacional.

He had won the 1989 Copa Libertadores the year before, saving four penalties and converting one of his own in a shootout win.

But it would be René’s high risk high reward philosophy that would ultimately send Los Cafeteros packing from their first World Cup in 26 years.

Donning the famous multi coloured triangular patterned kit with patches of traditional South American art on the front, the only thing crazier than René’s kit for this tournament was himself.

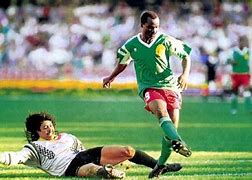

A win against The United Arab Emirates and a last minute equaliser against eventual champions West Germany in the group phase was enough to set up a round of 16 tie against Cameroon.

It was veteran striker Roger Milla who put the African side 1-0 up in extra time, beating Higuita at his near post.

A matter of minutes later, René had taken up a familiar position, storming out of his goal to sweep up an overhit Cameroonian pass, and began to exchange the ball with defender Luis Perea 40 yards away from his goal line.

“No Higuita! No Higuita! No Higuita!”

Colombia watched, amidst the desperate cries of the commentator, as Higuita was dispossessed by Milla, who calmly slotted into an open net.

A 116th minute goal from Bernardo Redín proved only a consolation as Colombia slumped to a 2-1 defeat in the Italian sunshine.

Despite his blunder, Higuita had shown his capability and comfort with the ball at his feet on the world stage for the first time, and it had turned some heads at FIFA.

The backpass rule which allowed goalkeepers to pick up the ball after it had been passed back to them by an outfield teammate was scrapped, aiming to reduce time wasting and encourage goalkeepers to play with the ball at their feet.

Higuita grinned when asked about the change in the legislation in his documentary “The Way of the Scorpion.”

“When they saw that I was playing, they met and said the goalkeeper can play. That’s why they call it Higuita’s rule, and that’s what I gave this world. I feel happy and proud.”

This completely revolutionised football, and paved the way for modern day goalkeeping, where comfort with the ball is a big virtue.

Putting the heartbreak against Cameroon behind them, Colombian earned the opportunity for redemption after they dismantled Argentina 5-0 to qualify for USA 1994.

However, they would have to do it without El Loco.

René had been jailed for seven months in 1993 for his role as a mediator in a kidnapping, and was considered unfit for the tournament upon his release.

When drug lord Carlos Molina had asked him to act as an intermediary for the transfer of ransom money to ensure the release of his kidnapped daughter from the hands of Pablo Escobar, René couldn’t exactly say no.

After all, it was a request that blurred the line between plea and command.

René’s pure generosity combined with the explicit implications of refusal led to him awaiting a call from the kidnappers, with a briefcase containing $300,000 in pesos to exchange for the young girl.

It seems odd that a drug lord would select a footballer for this task, but René was trusted at all levels of society in Medellín.

“He was seen as someone who wasn’t going to let anyone down, he was a trusted public figure,” says Mark Biram, author of Viva Colombia.

“It’s completely unthinkable for the background we’re from but, based on where he grew up, he just probably thought that’s what needs to be done, and he went and did it.”

“It was a mission from God,” René told the press at the time. “It was a very beautiful thing. I did it as a blessing, because God gave me the chance to make a family happy. It is not often in life that you get such a chance.”

It was in a hamburger restaurant that the ransom money was exchanged, and Molina’s daughter was collected and driven home by Higuita himself.

Despite René’s reluctance, he left the Molina residence with $64,000 stuffed in his pockets as a token of the family’s appreciation.

It was illegal to financially benefit from a kidnapping under Colombian law, and René was put behind bars, and would miss out on the upcoming World Cup in the States.

But not even two Higuitas in the Colombia goal would’ve saved the national team that summer.

Despite being tipped as favourites for USA ‘94 by Pele himself, Colombia buckled under the weight of expectation and the threat of cartel retribution.

Óscar Córdoba, René’s replacement, had a tournament to forget, and the squad returned to Medellín having finished dead last in their group, losing to host nation USA being the nail in the coffin.

“They went to the States under a lot of pressure because the cartels are betting heavily on them, and they just played within themselves, they didn’t play their normal football,” said Mark.

“The country is in chaos, there’s kidnappings and murders going on all the time, and they go to the tournament with that as the backdrop.”

Unsurprisingly, the cartels were unforgiving, and as retribution for his own goal in the 2-1 defeat to the USA, defender Andres Escobar was shot and killed by three men outside of a club in Medelíin.

Six bullets were fired, the assassin allegedly shouting “Goal!” every time he pulled the trigger.

“It was just a desperate lunge to try and cut the ball out,” Mark remembers. “What came next was truly tragic.”

In hindsight, perhaps René’s exclusion from the World Cup squad was a blessing in disguise, but either way he was still upset to have missed out on the opportunity to play for his country.

Things would soon improve for him though, and he lifted his first Colombian title with Atlético Nacional, and earned a recall back to the national team in the beginning of 1995.

The year had started well for El Loco, and it would end in the same vain, with René producing what is widely considered the most spectacular piece of goalkeeping in football history.

Jamie Redknapp’s wayward cross floated towards Higuita’s goal, and he opted for an alternative method to the standard catch and distribute. After all, that was what normal goalkeepers would do, and René Higuita was not that.

A sold out Wembley crowd watched in disbelief as René dove forward, flicked his legs back and cleared the ball with his heels.

He was grinning from ear to ear as he hoisted himself back to his feet after.

“They’ve always called me a clown, and here’s me proving them right!” René exclaimed as he watched the save back recently.

René represented 14 different clubs in his career, tested positive for cocaine whilst playing in Ecuador and underwent plastic surgery on live TV, claiming he was tired of being “ugly René.”

Still only 58 years young, Higuita is now passing on his wisdom as a goalkeeper coach at his beloved Atlético Nacional, meaning we could see another El Loco very soon.